傳統為引,陳旻的設計新語

這位常駐杭州、卻對香港情有獨鍾的設計師,擅長以中國傳統工藝為基礎,創作出具有全球影響力的當代設計作品。

陳旻剛從杭州抵港,便到香港一家咖啡館裡坐著,思考「橋樑」這個概念。他指的不是實際意義上的橋樑,而是連結不同時代、文化和創作方式的無形橋樑。他說。「我喜歡把自己想像成一座橋樑,將東方和西方、過去與現在、理念與現實連結起來。」

這正是他設計哲學的核心所在——力求打造既具創新性又根植於中國工藝世代的作品。他的早期作品之一——「杭州凳」——體現了這一理念,這款作品於2013年面世,並為他贏得了國際聲譽。「杭州凳」由16層僅0.9毫米厚的竹片製成,這些竹片被彎曲塑形成柔和的弧形後黏合,使凳面如同水波般流暢。一根竹竿穿透結構,連接兩端。

當你坐在凳子上時,凳面的弧度會隨體重調整,提供彈性支撐。這是傳統與創新之間的平衡,也是將竹子悠久的使用歷史轉化為明顯的當代風格。 陳說:「在中國,人們往往將設計視為一種風格。但對我來說,它是一種語言。」

陳此次來港是為了2025年設計營商周(BODW)峰會上發表主題演講, 但這只是他多次造訪香港的其中一次。儘管深植於杭州,陳卻對香港情有獨鍾。「香港正是東西方交匯的地方,」他說。「而且他們仍然保留自己的獨特風格,太有趣了。」

作為一名「80後」,他從小就接觸粵語流行音樂、香港電影和TVB電視節目——這足以激發他學習粵語的興趣。香港也對他作為設計師的成長中扮演著關鍵角色。陳至今仍記得他曾被設計師陳幼堅(Alan Chan)1997年的一張海報深深吸引,海報上米奇老鼠和唐老鴨裝扮成為經典武俠小說《西遊記》中的人物。他認為這是文化的完美融合。 「那一刻我就想,這正是我們應該做的」他說。

陳旻的設計之旅

陳於1980年出生,在一個充滿藝術氛圍的家庭中成長。他的祖父是一位木刻版畫家,他有兩位叔叔擔任設計教授,其中一位任教於荷蘭的埃因霍溫設計學院(Design Academy Eindhoven),陳也曾在此修讀設計學士學位。之後,他前往米蘭多莫斯設計學院(Domus Academy)攻讀碩士學位,並在畢業後留校擔任助教。 2010年,他回到中國,兩年後創立了自己的工作室──陳旻設計有限公司。

陳認為家鄉杭州對他的設計理念產生了深遠的影響。「杭州人總是很放鬆」他說。「他們從不匆忙。」當地還有近在咫尺的自然風光:「你開車大約10到15分鐘,就會發現自己被大自然包圍。這在中國城市裡實屬難得。」

這種與風景的連結讓他恢復了心神。米蘭設計周結束後,他經常逃往阿爾卑斯山。有一次,他被困在瑞士的雪中,感受到「人是多麼渺小」。這堂課深深烙印在他心中:「有時候你可以忘掉設計,思考如何作為人類生存。」

這種腳踏實地的心態讓他保持平衡──尤其因為上海這裡只有很短的火車車程。既方便商務往來,但其遙遠的距離又能讓陳有思考的空間。 「這成了我逃避會議、設計活動或其他事務的好藉口。」他笑著說,「我會說,抱歉,我在杭州。下次吧。」

杭州作為知識分子和藝術家的聚集地,擁有悠久的歷史,同時也是思考設計與工藝關係的沃土。陳回到中國後,發現自己面臨著一個許多訪客都會注意到的的矛盾:中國是一個擁有數千年歷史的文明古國,但能讓人感受到這段歷史的物質遺存卻出奇地稀少。 「很多人來中國後都說,他們以為這是一個擁有五千年歷史的國家。」陳說:「但走在街上,你很難找到一座超過百年的建築。」

為了解釋這種脫節,陳追溯到文化創造的根源。他說,在歐洲,「創造力是從0到1演變出來」——發明、顛覆、大膽飛躍。相較之下,中國的發展則是透過「重複和模仿」慢慢累積出來,類似於「基因突變......DNA裡一個細微的細節都變了」。他堅持認為,這並非簡單的複製,而是精益求精:「我們總是模仿。我們總是遵循大師的教誨。然後,在這個過程中,我們會想,啊,這裡或許有些地方我可以改進。」

對陳來說,「更新」不僅比「創新」更準確,也更誠實。這也解釋了傳統可以變得脆弱:一旦重複鏈斷裂,知識便會迅速消散。

他親眼見過。有一次他拜訪絲綢製造商時,對某些古董布料的稀有性感到震驚。「我很驚訝他們告訴我不能重複製造那種布料,」他說。「科技如此先進,他們仍無法複製——僅僅因為知識和技能已不存在。」

新舊交融

陳說:「藝術、設計與工藝之間的界線越來越模糊。」他表示,消費者越來越在所購買的物品中尋找身份認同與意義。「我們其實不需要像以前那麼多工業化產品了。」手工製作的物品帶來工業產品所缺乏的溫暖——一種由材質、工藝與人性觸感孕育而生的共鳴。

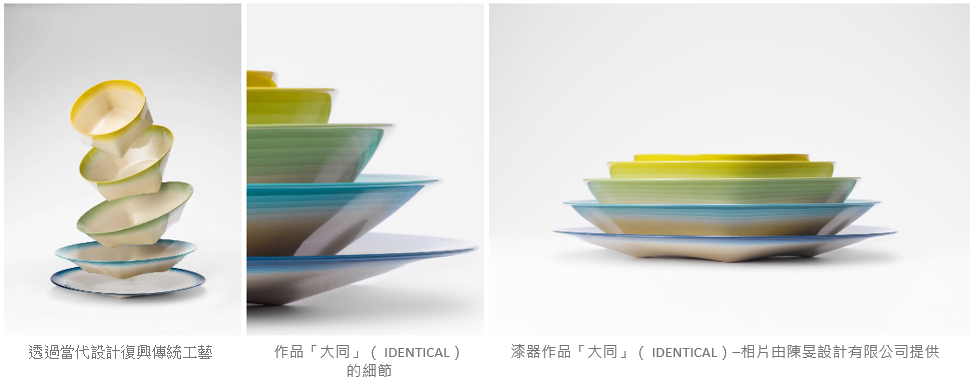

這種跨學科的融合啟發陳創立了平台neooold,自2020年啟動至今,持續以當代設計復興傳統工藝。他匯聚來自世界各地的設計師、藝術家與工匠,運用中國技藝如石雕、漆器、絲綢及木工,創作跨越地理與文化的新作品。

陳如此專注於手工製作,卻對人工智能抱持著出乎意料的樂觀態度。他不僅不認為人工智能會威脅傳統工藝,反而將其視為一種能夠重現失傳技藝的工具——古代知識的智能助手。

例如日本京都有一位以『聽聲辨質』鑑定銅茶罐而聞名的工匠大師,想像一下如何運用他的寶貴知識、經驗用作訓練人工智能。」「換作我,一定會用 AI把工匠的話語,甚至動作全程紀錄並作分析。即使他離世後,我們仍能掌握他的知識。」這是一個傳統與新科技不再是對手,而是合作夥伴,彼此成就的願景。

陳近期的家具設計項目體現了他對融合與永恆之美的追求。去年,他挑戰自我,將中西長椅的設計概念融合──既要體現中國傳統座椅的輕盈靈動,也要展現歐洲教堂長椅的莊嚴氣勢。

成果始於一個極簡模具,塑造出部分靈感來自造船與飛機翼的弧形膠合板外殼。「當兩道曲線相交,便會形成這樣的空間結構,」他說著,雙手形成一個看不見的弧線。「裡面是空心的,所以很輕,但非常堅固。」

見過原型的人很難從風格上為它下定義。 「他們無法判斷。它看起來像斯堪地那維亞風格(Scandinavian),或者有點日式風格……但它又屬於任何地方。」這種普遍性反映在陳為這款長椅起的名字上,它就叫《一片木頭》。

陳的做法吸引了全球頂尖客戶青睞,包括Nike和IKEA。他目前正與中國奢侈品牌SHANG XIA進行重大合作,品牌正將重心轉向生活風格與家具。「我們正在為SHANG XIA打造一個全新的『家』」他說。展品將包括漆器、融合中法風格的碳纖維座椅,以及模組化層架系統——系列總計包含超過20件家具。

同時,neooold正籌備明年春季在米蘭的國際首秀,屆時將展出其首個跨文化駐場團隊的作品,團隊包括荷蘭設計師、意大利建築師和日本工匠。之後,他將著手籌備neooold的首個展廳,預計於2027年在紐約開幕。

這將是他設計語言發展歷程中的重要新階段,這種語言建立在延續而非斷裂、傳承而非創造之上。它並非拋棄過去,而是對其進行更新——以一種微妙、智慧且永無止境的方式。

陳旻於設計營商周(BODW)2025峰會發表題為《傳統的未來式》主題演講,分享其身分與創作實踐如何成為連結古今的橋樑,將傳統帶入當代,而香港亦是他的重要靈感來源之一。立即到bodw+重溫完整主題演講!

撰稿: Christopher DeWolf

本文與網絡雜誌Zolima CityMag合作發表。Zolima CityMag 專注報導香港的藝術、設計、歷史與文化。